There’s no doubt that people in New Zealand (and around the world) are getting fatter. One reason could be what’s known as ‘portion creep’.

We’re an obedient bunch — we eat everything on our plates, just as our mothers told us to. The problem is, over the past two decades, the portions we’re serving (and being served) have gradually increased in size.

Today, health experts view this ‘portion creep’ as the key to our global growing weight problems.

This super-sizing isn’t just an American phenomenon. The problem is prevalent here, too, in all manner of ways. So how did this happen?

What’s changed?

Back in the ’60s, the diameter of an average dinner plate was about 25cm. Today, it’s more like 30cm. It doesn’t sound like much of a difference but according to an Australian study those extra centimetres can potentially see our dinner plate kilojoule capacity surge by roughly 60 to 100 per cent.

This change would be okay if we were plating up our food in tasty measured morsels as top restaurants do — but we’re not. And numerous studies show that the more food we pile on our plates, the more we eat. In fact, a recent study showed that when researchers served adults a large portion of pasta, they ate 34 per cent more than when they ate from a smaller bowl.

Why don’t we just eat less?

“The idea that larger portions provide more energy may seem intuitive but most people tend to eat whatever they’re served,” says dietitian Alice Gibson from The University of Sydney’s Boden Institute of Obesity, Nutrition, Exercise & Eating Disorders. “We’ve become so accustomed to larger serves that a ‘normal’ portion is often much more food than we actually need.”

Indeed, we have become so used to seeing — and eating — a generous portion that we can feel disappointed or worry we will go hungry when we’re served a smaller piece of the pie. This may help explain why so many of us disregard the recommended serving sizes on food packaging, or simply why we overeat. We might eat a whole pizza when a healthy serve is two medium slices, for instance, or fill our breakfast bowl with double the appropriate serving size of cereal.

To make things worse, food marketers and manufacturers are cleverly exploiting our anxiety and confusion. By offering the same product in a range of sizes, they are able to charge only a little more for the larger packet, making it seem like good value.

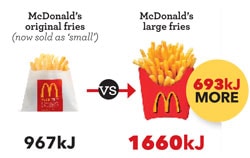

For example, when McDonald’s first opened its golden arches, it offered just one size of fries. Today, the company describes that same size as ‘small’ (967kJ), and its menu features two more sizes: ‘medium’ (1380kJ) and ‘large’ (1660kJ), a 72 per cent increase on the original ‘small’.

We’re drowning in drinks, too. Check the nutrition-information panel of any beverage, and you will notice that the recommended serving size is not always the same as the bottle’s actual size. The smallest Coke can at 250ml contains 450kJ but a 600ml bottle often found at the corner store is a whopper that’s fizzing with 1080kJ.

How everyday foods stack up

Fast food isn’t the only fare that’s getting in on the act. While some pantry staples remain unchanged, other essential basics are now jostling for more shelf space. Even the humble slice of bread is available in bigger-than-before versions. Picturing two larger slices with extra fillings gives you the idea — that’s an old-fashioned sandwich-and-a- half!

There has also been a massive increase in the number of café snack products, many of which come in bigger sizes to start with. A standard cookie from a multipack still weighs about 10-12g, but a luxury cookie from a coffee shop can weigh in at a hefty 110g — and carry about 10 times the kilojoules.

A licence to overeat?

Beware the portion creep with so-called healthy foods as well. In a recent UK study, adults served themselves larger helpings of the cereals, drinks and coleslaws they considered healthier than these foods’ standard alternatives.

The researchers also found that even a meal’s description has a negative impact on portions. When they served both healthy and overweight adults identical lunches on three separate days, subjects ate significantly more when told the meal was low in fat and kilojoules than when it was described as high in fat and kilojoules — and consumed an extra 163kJ as a result.

Being aware of the tricks that our minds (and some food manufacturers!) play is the first key step towards whittling our waistlines.

We need to watch out for the same thinking when we see ‘healthy’ sounding treats in cafés, too. Labels like ‘raw’, ‘paleo’ or ‘gluten-free’ don’t necessarily mean something is any healthier (or lower energy) than the regular versions.

How to practise your portion control

1. Say no to bigger bargain sizes

Whether we’re at the supermarket or a fast-food outlet, we all want good value for our money when buying food. Upsizing and opting for value meals may mean you get more food for only a small increase in price but what about the increase in your waistline? It can be difficult to push the pause or stop button once you’ve pressed play, and your focus is eating that entire upsized serving of food. Don’t be tempted by bargain buys – bigger isn’t better.

2. Be portion savvy

If you do buy bargain-size supermarket foods, create better portions by dividing the contents into smaller amounts. For example, try using reusable containers or sealable bags to portion out 30g nuts (about 10-15 nuts) from a larger bag. Keep large food packets away from the kitchen table and store leftovers in the fridge before you sit down to eat. This saves you from going back for seconds (or thirds).

3. Downsize your plates and bowls

The size of your plate is one of the biggest factors influencing the amount of food you eat. Eating pasta from a small bowl not only means you will eat less, but it also seems more satisfying than eating the same amount of pasta from a large bowl. If your portion looks too small in a large bowl, you’re more likely to pile your plate high with extra pasta — and finish it, too!

4. Use smaller cutlery

You can still delight in indulgent desserts if you scoop them up with a smaller utensil. Spoon for spoon, you will consume fewer kilojoules than you would using a standard dessertspoon, without having to compromise on satisfying flavour.

5. Design your own plate

Buffets, barbecues and casual dinners can be traps, encouraging you to eat to excess. When faced with the option to serve yourself, fill half your plate with vegetables and salads. These low-kilojoule choices satisfy you and leave less room on your plate for more energy-dense foods such as bread, meat and potato.

6. Eat mindfully

Have you ever wolfed down an entire plate of food without giving the flavours and textures a thought? It’s so easy to overeat when you’re not focusing on your food. Take time to savour each mouthful and avoid distractions such as watching TV, chatting on the phone or driving. Simply listening to your body’s hunger cues helps you avoid over-eating.

Bigger than bite-size

The larger the portion, the more food we load onto every forkful and cram into each bite. That’s been the finding of many studies, including an analysis of US childrens’ eating behaviour. When researchers served kids larger portions, they ate 25 per cent more food and also took larger bites. (The average bite was 12 per cent bigger.) Tellingly, when the children served themselves, they ate 25 per cent less food.

Why can’t we ban oversized foods?

Some health authorities have become so concerned by portion creep that they’ve called for government legislation to regulate the portion sizes that fast-food chains and food manufacturers can sell. Just last year, New York mayor Michael Bloomberg tried to ban fast-food outlets from selling super-size soft drinks. His efforts led to cries of ‘nanny state’ and ‘food police’, and the high court ultimately overturned his law, arguing that the ban restricted free trade: the convenience store next door could lawfully sell a one-litre bottle of the same soft drink – it just didn’t have a straw in it.

Check that serving size

If you read the nutrition information panel to find out how many kilojoules or grams of sugar you’re eating, well done. If you forget to check how many servings there are in the pack before you read the per serving column, you could be in for a surprise!

There are no guidelines for manufacturers when deciding on the serving size, and some are more realistic than others.

A 45g Kit Kat is listed as two servings. If you eat one serving, that’s 490kJ. But if you eat the whole thing (let’s face it — not hard to do), that’s 980kJ.

Portion size: The new normal

Many of the foods we eat today and accept as ‘normal’ are actually supersize versions of what people considered normal 20 years ago.

Fast fact: In a 2011 study, scientists set out to look at how accurately we can assess the size and, more important, the kilojoule content of fast foods. The average gap in people’s guesstimates? A shortfall of nearly 4000kJ.

www.healthyfood.com