Gillian Eadie, managing director of the Memory Foundation, shares how to boost and protect your memory.

An active, alert memory is not only about recalling facts and figures, remembering appointments, or always knowing where to find your car keys. Recall also relies on what you believe about memory, your level of confidence and personal happiness.

Memory is a faculty that can be improved with practice and is also supported by many other key factors – mental agility, nutrition, exercise, rest, paying attention, controlling stress, as well as understanding and using skills to enhance memory performance.

Your memory is your life

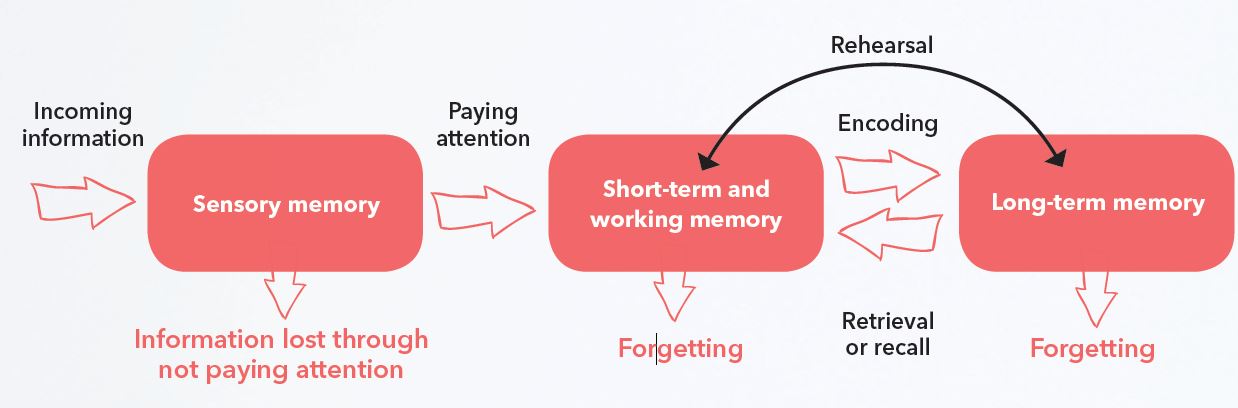

Today we are surrounded by information – information that comes from conversations with others, what we read and watch, the content we are exposed to on social media, emails, phone calls, texts and everything that we taste, touch, smell and feel. It is estimated that we interact with around 34GB worth of data a day and most of this reaches your sensory memory for just a few seconds before being discarded.

Your brain can manage around seven items of information in your short-term memory at a time. What happens to all of the rest?

It is ‘forgotten’. Forgetting or discarding is how your efficient brain protects you from overload.

So paying close attention to what is important to you is the way to ensure that that information will be processed and kept.

Memory improvement comes through applying techniques for paying active attention to information you want to recall later.

Occasional memory lapses do not mean memory loss

Everything you have learned, know how to do and have encoded in your long-term memory is still there, safely stored in the cerebral cortex, the 3mm outer layer of neural tissue encasing the brain. We do not ‘lose’ this information – what can happen is that connections we use to access the information may become slower or out of shape.

Forgetting and misremembering are normal parts of everyday life – at all ages. Cognitive changes, including changes to memory, begin for many people from the age of 40 or 50, and often become more noticeable in the 60s and beyond.

Understanding how memory works and the steps that can be taken to sharpen recall skills will improve memory confidence and overall brain health.

What’s the difference between short -and long-term memory?

Memory is not one single process but a series of interactive processes, beginning when you are exposed to a new sensation, fact or idea for just a few seconds in the sensory memory.

Anything you sense and pay attention to will pass from the sensory memory into the short-term memory for a maximum of 20 to 30 seconds. This is where you have the opportunity to process the information by repeating it, writing it down or studying it closely. Without this activity, details are quickly forgotten.

Have you been introduced to someone by name, only to have it promptly vanish out of your head? That is your short-term memory filter in action!

Concentrating on information that is important to you will create a memory trace and ensure its passage to the next stage – being encoded into the long-term memory.

It takes around seven seconds to create a reliable memory trace (or connection), which the brain uses to store the new information. This time is pivotal for memory because without active creation of memory traces, there will be nothing for the brain to process. Circuits of neurons in the brain (neural networks) are created, altered or strengthened to store new information in the long-term memory where it can stay intact for a very long time.

Rehearsing the information by telling someone else, recalling it later in the day or reusing it in a different way will strengthen the neural pathways and sharpen your recall.

Is it possible to have a photographic memory?

Science tells us that the idea of a ‘photographic memory’ talked about in fiction does not exist. However, eidetic memory – where some people can retain images in the sensory memory much longer than is usual, creating a memory trace for later recall – has been observed.

Most of us can recall visual information in more detail than other kinds. For example, we remember a face much more easily than the name associated with that face. But this isn’t really a photographic memory; it just shows us the normal difference between verbal and non-verbal memory skills.

Why do we forget things?

Memory sometimes lets us down. There are many reasons for this, getting older being just one of them.

In the late 1800s, German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus first described the Forgetting Curve and demonstrated that, over time, we lose 90 per cent of information we encounter if we make no effort to retain it.

For accurate recall, the brain needs strong, active neural pathways to store information. Throughout life the brain needs to be challenged to keep these neural pathways active. Without deliberate mental exercise and stimulation, remembering can take longer.

Memory let-downs can also be attributed to not having paid close attention at the time of storage. Similarly, not enough associations or cues can make remembering difficult (eg, naming the other children in your new entrant class is much easier if you can see a photo of the group. The image provides a memory cue). Some stored knowledge, such as the French you learned at school, fades in time but it is surprising how quickly you can activate the connections when you visit France again.

Stress is the enemy of memory

The cortisol and adrenalin stress hormones released during times of strong emotional responses, stress and anxiety cause the brain to enter ‘fight or flight’ mode, which interrupts the normal sequence of memory processing.

Overloading the brain with too many short-term memory items will also cause details to be lost.

Being easily distracted and finding it difficult to concentrate can affect the strength of the memory traces we create. That is why trying to do too many things at one time, or multitasking, is another enemy of memory.

Brain injury, some medications and depression can also affect the memory process.

Why we tend to be more forgetful as we age

Forgetfulness may come about because people expect to lose memory confidence ‘because they are getting older’. It becomes much easier to ask someone else or excuse lack of mental effort with phrases such as, “I’m having a senior moment”. This attitude is a tragedy because neuroscientists now know that new dendrites (where our neurons receive most information) grow for the whole of life when the brain is challenged.

Jian Guan, of the Centre for Brain Research at the University of Auckland has conducted extensive research into why brain performance may decrease with age. Dr Guan identifies four main categories of factors, only one of which we cannot personally influence: the age-related hormones that give us grey hair and other age-related biological changes.

The other groups of factors in brain ageing are:

- Having a sedentary lifestyle

- Lacking enough mental and physical activity

- Poor nutrition, obesity and other related medical conditions

Making a determined effort to remedy these three will result in increased memory confidence, independence and productivity.

Daily habits that support an alert memory

- Have a positive attitude

- Engage in life

- Take exercise Increase your daily water intake

- Eat your way to a youthful brain with a good balance of protein, good fats, carbohydrates and vitamins. Include salmon, tuna, walnuts, linseeds and antioxidants in your diet

- Have healthy snacks on hand

- Seek a mental challenge every day

- Manage stress and practise relaxation

- Sleep well

- Thrive on learning

What we can do to boost our memory at any age

- Your most important memory asset is a positive attitude. Don’t excuse yourself by saying, “I never remember names”. Learn the strategy for reliable name recall.

- If you find something new that you want to remember later, give your brain as many ‘hooks’ or memory traces as you can. Using repetition, actions or taking a ‘mental photograph’ you connect what you need to remember in as many ways as possible to things you already know. These connections form neural pathways to the information.

- Learn more about the brain. A basic understanding of your brain will help you work in ways that support thinking and problem-solving. You have billions of neurons and synapses (‘brain cells’ and connections) firing even when you’re sleeping. Use them to your advantage.

- Look for ways to challenge your brain. Learn something completely new to you. New neurons and dendrites grow every day when your brain is firing. How long they survive depends on how actively you use them.

- Take care of your nutrition. The brain weighs only 2 per cent of body mass but consumes over 20 per cent of the oxygen and nutrients we take in. Eat moderately and include brain health-supporting foods in your diet.

- Laugh out loud and often. Laughing and humour helps you keep things in perspective.

- A gentle walk for 20 minutes a day will promote vascular (blood vessel) and neural cell regeneration according to Dr Guan.

- Don’t skimp on sleep. Important storage and cleansing activities occur in the brain while you are sleeping.

- Develop and maintain friendships. Everyone needs social interaction for resilience and mutual support.

Five quick brain kick-starters

- In reverse order, spell your name and address out loud.

- Visualise your telephone number. Now randomly add, subtract, multiply or divide the numbers.

- List 10 words from a news item or book, study them for 30 seconds; hide the original and write down as many of the words as you can recall.

- Easy challenge: quickly sketch the layout of your kitchen, from memory. Harder challenge: sketch the layout of your local library, café or other public place you have visited recently.

- Count backwards from 100 in groups of 7. “100, 93…”

Related links

For articles, brain games, brain training and a monthly newsletter

memory.foundation

brainfit.nz

“My short-term memory is shot. I can’t remember what I had for breakfast!”

This is a myth. Short-term memory describes items fleetingly in your memory right now. If the speaker hadn’t focused on eating their breakfast at the time it would not have been encoded as a long-term memory.

Article sources and references

- Guan J. 2015. Centre for Brain Research, The University of Auckland and Memory Foundation. Why Your Brain Needs Exercisehttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SAxodM-kMEU

- Lamont AC & Eadie GM. 2014. 7-Day Brain Boost Plan. How to become Brain Fit for Life. Memory Foundation

- Lamont AC. 2006. Cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses of the effects of aging on memory in healthy young, middle-aged and oldest-old adults. PhD Thesis, Massey Universityhttps://mro.massey.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/10179/258/02whole.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Memory Foundation. How to Make Memory Traceshttps://memory.foundation/2016/01/29/memory-traces/

- Salthouse TA. 2016. Continuity of cognitive change across adulthood. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 23:932-39https://link.springer.com/article/10.3758/s13423-015-0910-8

- SharpBrains. Neuroplasticity: The potential for lifelong brain development, sharpbrains.com Accessed May 2019https://sharpbrains.com/resources/1-brain-fitness-fundamentals/neuroplasticity-the-potential-for-lifelong-brain-development/

www.healthyfood.com